“Working Capital” – A Hot Topic in Every Business Acquisition

Working capital is the backbone which supports a company’s day-to-day operations. It is generally best represented by the company’s current assets less its current liabilities. It is also a major source of confusion and frustration in business transactions.

In any business acquisition evaluation, it is critical to understand a business’ sources and uses of working capital because it directly impacts cash flow. For example, one company may collect from customers in 60 days of delivering products/services while having to satisfy vendor obligations within 30 days. Contrast that working capital environment with one in which collections are made within 30 days. From a P&L perspective, these two companies can look identical, but their cash balances would be very different.

Addressing working capital early in the transaction process is critical. Too frequently, the topic of working capital is introduced too late and the confusion created can slow the process and potentially even kill a viable deal.

The overarching working capital question in any business acquisition is “How much, if any, working capital needs to remain with the business at Close.” In general, the answer is that Sellers should be prepared to leave the amount of working capital that it typically maintained to generate the earnings that the Buyer used to value the business.

The standard market approach is for Buyer and Seller to agree upon a pre-determined level of working capital to be delivered with the business at Close. There are different methodologies and approaches for determining the amount, but the most common is to use a historical average over the trailing 12 months (this assumes valuation is a multiple of the trailing twelve-month EBITDA). This is a rational approach, as a Buyer is paying a multiple of the earnings power of the business. To generate that earnings power, there is an inherent level of working capital required by the business.

An analogy is a car purchase. When you evaluate a car (including the test drive), you expect gas, engine oil, windshield fluid, radiator fluids, etc. at normal operation levels. When it comes time to own and take possession of the vehicle, you expect those same items to come with the vehicle such that the car is delivered to you in the same fashion in which you evaluated and drove it. If the car was provided to you without the gas, oils and fluids, you would expect a price reduction to cover your cost to provide those. In this analogy, the gas, engine oil and fluids are the working capital in a business acquisition.

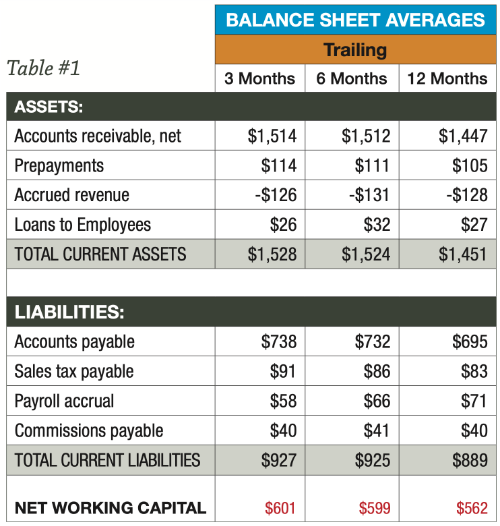

For an illustrated calculation of working capital using the standard market approach, refer to Table #1. This Table illustrates how after excluding cash and interest bearing liabilities, the sample company carries approximately $600k of working capital. Under the standard market approach, this would be viewed by both Buyer and Seller as a reasonable pre-determined level of working capital to be delivered at Close. Tactically, the closing balance sheet is estimated at the time of the Close and any difference between the estimated amount and the pre-determined amount is treated as an adjustment to the purchase price. Eventually, typically within 90 days of the Close, there is a look back to true up the closing working capital to reflect actuals.

This approach is viewed as fair and protective to both the Buyer and the Seller. The Seller gets a multiple of the earnings and the Buyer gets a business with all the components in place. By setting the working capital amount, both parties are protected from large swings in working capital at Close. For example, if working capital at Close is greater than the pre-set amount, the Seller recovers the amount of the overage. This scenario could arise as collections of receivables gets neglected leading up to close. Buyers are protected from the Sellers collecting all receivables right before Close (as Sellers generally keep their cash as part of the transaction) or deferring payments leading up to Close. In either of those situations, working capital at Close would be lower than the pre-set amount and the Sellers would be required to remit cash to the Buyer at the settlement time.